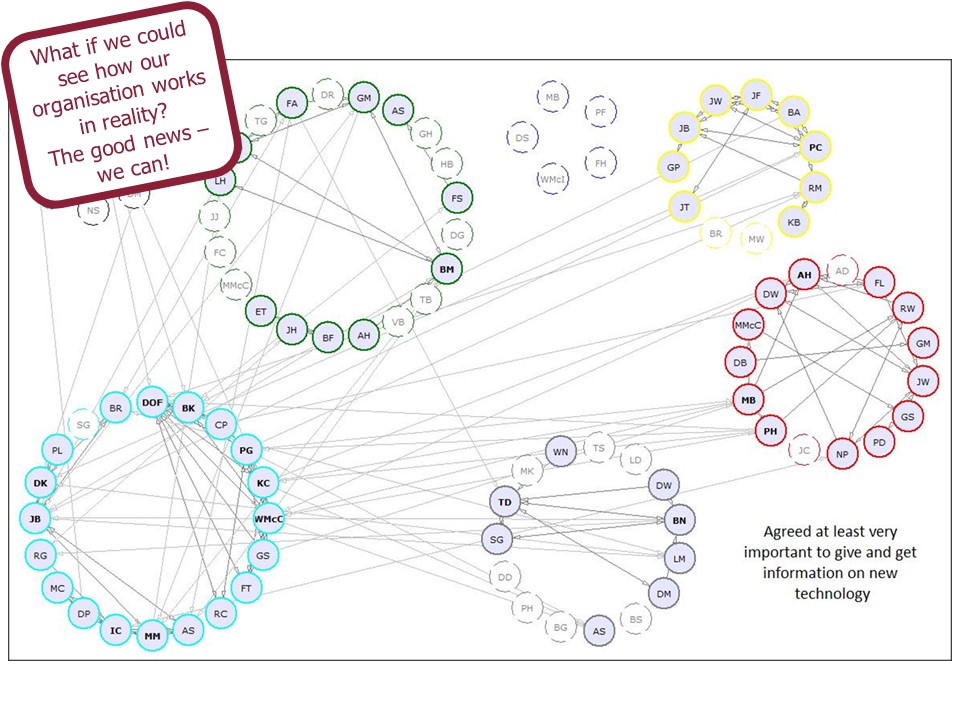

Gaining visibility of the Informal networks that exist in your organisation can unlock your people’s untapped human brilliance.

Continue readingWhy do Employee Engagement efforts fail to engage?

If your efforts to improve employee engagement aren’t getting results, here are some reasons why and what to do instead…

Continue readingGreat performance comes from flow

Sometimes teams just click. Most of us would recognise that those virtuoso performances come from a place of deep mutual understanding, connectedness, and alignment to a shared goal or purpose. However, there are some other vital ingredients which, are universally important and often neglected.

In your teams, have you ever noticed…

- Conversations not being as equal as they might be, a view or individual dominating

- Resorting to “decision by exhaustion” or “decision by senior status / authority”

- Conversations in deadlock, cycling round without resolution and progress

- Relationships being unnecessarily tested, often through misunderstanding

- Lots of views exchanged, not so much progress

- People feeling they’ve not been heard and understood

- Some people holding-back valuable contributions

- Introverts sitting in resentful silence

And then wondered why there is a lack of buy-in to the process, the output, or even the team itself?

Introducing Teams in Flow (TiF)

What could your team achieve if…

- There was a positive and cohesive climate

- Decisions got made with more speed and less friction.

- There was greater psychological safety; more innovative ideas, energy and engagement

- Buy-in to decisions was improved, even by those who offered alternatives

What is the magic ingredient?

TiF is all about improving our interactive skill in conversations. It is well proven with a rigorous research base.

TiF is a unique blend of two threads of research and our own subsequent in-use refinements that span decades. One thread is behavioural, it relates to the conscious skill set that enables participants to engage with others in conversations which flow, are generative, equal and engender psychological safety. The other essential ingredient is a guide-rail to structure the conversations – idea generation, decision-making and problem-solving are structures that apply most often in the work of organisational teams. Both threads are necessary, neither one is sufficient.

TiF results in enduring behavioural change

Skills are only learned, embedded and become habitual through cycles of practice and feedback. The TiF intervention is all about creating a safe place for the team to learn together through practice. It is vitally important that the content of the discussion is real and meaningful to the team. The happy consequence of this is that the “real work” of the team gets progressed at the same time the team is acquiring the new skills. By virtue of working with every-day teams peer-to-peer feedback and support endures long after the learning experience, sustaining the behaviour change.

Extraordinary results require a radically different approach

Here at Organisational Vitality our purpose is to help leaders and their teams liberate their full potential; to have fun doing their best, most rewarding work; and to enjoy ever-improving performance.

We are very comfortable being an outlier to the majority of providers in the Organisational Development space. We don’t follow the crowd. Challenges in organisational dynamics are, by definition, wicked and messy, and yet most providers offer simple, unresponsive solutions that are incapable of dealing with that inherent complexity.

We have optimised to serve organisations that are purposeful, progressive and those that are scaling. We offer highly personalised service, value the relationships we hold with those we serve, and based on our unique diagnostics and interventions co-create healthy participative change in organisations.

Curious to know more?

We would love to hear from you. The conversation could change the flow of your team – forever!

Is it time you cleared out the “deadwood” in your organisation?

Springtime is the right time to get out in the garden with the pruning shears and reshape your fruit trees ahead of their next phase of growth. We imply something similar when we talk about “deadwood” in the context of organisations. Only we are talking about people not vegetation.

What or who is for the knife?

Deming observed that 95% of performance (good or bad) results from the system and only 5% from the people. Following that theme this post will present the idea that it is “the system” that we should be attacking with a sharp instrument, not human beings.

Why change the system?

When we first completed the research that underpins the Vitality Index it was way back in 1990. In 2010 when we reran the research, on aggregate and based on the organisations in our samples the Vitality of UK organisations had dropped by something like 5 percentage points.

“Vitality” is an umbrella term that we use that encompasses employee experience, adaptability, and ability to innovate.

We package these three things together because they are the unavoidable consequences of a set of 26 practices that our research identified.

If you adopt the practices, you will get these outcomes – all of them; you can’t pick and choose – sorry.

What changed between 1990 & 2010?

The rate of change, that’s what.

A lot happened between 1990 and 2010. The internet happened for a start and brought with it entirely new ways of doing business, building relationships, communicating as well as opening-up a whole new world of easy-to-access information. This combined with a whole heap of other new technologies meant that the rate of change in the external environment accelerated to a whole new level. And yet in the same intervening time the ability of our organisations to adapt deteriorated. And that in spite of the zillions of words written on the subject of how to manage change in a VUCA world.

If the world was speeding up, why were organisations slowing down?

This is the $6M dollar question. Our research was able to indicate and broadly quantify the slow-down but was not designed to identify the why.

Based on our observations however, we have a hunch. In this time organisations seemed to get taller, with more layers of management, and wider with much more functional specialism (i.e. in these two decades procurement became widely professionalised, the ratio of HR people to numbers employed exploded). So much more of everyone’s work was done within the constraints of an IT system (great for visibility, efficiency and consistency, not so good for continual improvement and adaptation). Industrial regulation widened to affect more sectors and deepened in its complexity and implications. A net result of all of these, and other factors, is that organisations became much more cumbersome, getting things done was rarely straight forward. The risk aversion of leaders also infected the mindset of anyone in the organisation with decision authority . Thus, to “prevent the worst happening”, processes, procedures and rules proliferated, and decisions got slowed by passing them up to the boss.

Sorry for the loaded question, but what do you think the net effect of all of these factors might be on an organisation’s ability to offer a great employee experience, to be nimble, adaptive and to innovate?

What is bureaucratic drift?

Processes, procedures, rules and authorisation levels all have their place, but have you ever noticed how much more common it is for process and procedure to get added and for rules and authorisation requirements to tighten than it is for them to be removed or relaxed? In the absence of this removal / relaxation activity, year on year, the level of bureaucracy grows without anybody really noticing, a bit like boiling a frog. So, unless there is a routine and deliberate effort to prune back the ever-expanding bureaucracy, we should expect our organisations to fall into a state that we call bureaucratic drift, becoming more and more bogged down in resource sapping and unrewarding activity which is of questionable value.

How might we go about the job of pruning?

When teams in organisations use the Vitality Index, we help them make changes in the form of safe-to-try experiments. Thanks to the research-based diagnostic capability of the Index, the teams are directed towards specific areas of practice that have the greatest potential for each individual team. Drawing on the knowledge contained in the Vitality Playbook, and the tacit knowledge in our heads, we offer some ideas to stimulate their own suggestions. We always encourage the team towards changes that lighten the bureaucratic load, rather than add to it. Here are some examples:

- Rather than adding a new report, meeting or agenda item, how about removing something that seems to add no value and see what happens?

- Search for and scrap processes / systems that have become institutionalised – the ones that may have had some value in the past but have outlived their ‘see-by-date’.

- Locate processes that are justified under the name of ‘control’ and check to see what actual control there is. Or do we just have the ‘illusion of control’ but none in reality?

- Check the ‘earners and spenders’ ratio. Earners are the people who generate the organisations income and add value to customers. Spenders do not. Shift spenders to more added-value roles, especially those that add value to customers.

- Crowd source to find out what is currently most difficult for and frustrating to employees and what they would like to see changed. And then engage them with the change process, from the why to the what to the how.

- Check to see how time is occupied with routine, repetitive activities – that are a bit like running hard on the spot, but don’t generate forward movement. Then engage people in stuff that will improvement performance in some way – the one-off tasks and events that will create movement

- Search for opportunities to replace tight, prescriptive rules with broad guidelines – and work out with the people involved what they should be.

Be bold; unlike the work of secateurs, pruning bureaucracy is reversible

“Safe-to-try” is the key here, all changes can be made in some way partial, time bound or reversible, so in way there is nothing to lose and learning is guaranteed. So no need to be timid, be radical. Unlike other forms of pruning accidents you wont be left trying to re-graft limbs onto trees or losing the wrong people.

Be bold, explore, experiment, have fun and whatever you do, don’t drift into a place you don’t want to be.

This post was written by Ben, he likes nothing more than helping with teams as they bushwhack their way through the bureaucratic entanglements that frustrate them and stifle the organisations’ performance.

Can we survey our way to better employee engagement?

From a Gallup report issued in 2022, there was this conclusion: “Employee engagement levels in the UK are one of the worst in Europe with fewer than one in 10 UK employees feeling enthusiastic about their job.”

In the old days there were attitude surveys, and they just about always resulted in some sort of report. Today they are called employee engagement surveys, and now sometimes employee experience surveys, but little has changed except the name. Otherwise, the issues remain – including one over-riding thought. If employee engagement surveys are such a good idea, how come there is still a problem?

Time for an explanation and some thoughts on how to do better?

Just get some data and make some changes

The logic is fine; survey our people, get some data, use data to change some stuff, employee engagement improves. Except, in practice, according to Gallup at least, it doesn’t. “Employee engagement levels in the UK ranked 33 out of 38 European countries, and suffered a two-point drop in score compared with last year’s survey.” If anything, it looks like it might be getting worse. The good news, and goodness we need some, is that more and more organisations are taking this issue very seriously; the fact that we haven’t “shifted the needle” has in no way deterred us from trying. Also encouraging is the recognition of the need for good data to guide decision-making. However, employee engagement is a complex output formed in an emergent way from many complex inputs, and will never be resolved through simple, one-dimensional actions.

But what data and what changes to make?

What are reports for? If this is not clear, known and accepted by all, from the outset, and nailed down through some sort of charter, then it is highly likely that the purpose will either get distorted or forgotten completely. In those circumstances, it sounds like another heavyweight report consuming loads of storage space and producing little in return. Defining a clear purpose might seem like an indulgent use of time, but it is essential to staying on course.

Once purpose is clear, it will probably be possible to answer some more key questions: Who is in the target audience? What are their goals? How is the report supposed to help them achieve their goals? Clarity here will help with making important design decisions, not only about the survey itself and the report generated but even more about the process by which the data is reviewed, analysed and used to design and implement improvement action. Without that action there is little or no chance of anything actually getting better.

If the response rate to your current survey is in decline, take this as a strong indication that a fundementally different approach is required.

And who should make the changes?

Another key question to help with those design decisions: is the report something that is ‘done to people’ or is it something that helps the employees themselves to identify and address the issues that need attention? If the target audience is only managers (or even worse only select managers) don’t expect a lot of improvement action. The ‘iceberg of ignorance’[1] will strike here. As a generalisation, managers do not know what the key, operational issues are in their organisations – and they will know even less about the causes of those issues. More of which later.

Then there is the risk of the report’s existence becoming an end in itself – another box ticked every year or two. And the longer and more glossy the report is, the less likely that action will result. Managers are busy people – however pretty the report may be, if it is long, there is little chance that it will be read and studied – and even less that it will stimulate improvement action. And if the report does not result in some sort of improvement, then what is the point of the report?

[1] The “iceberg of ignorance” is a concept popularized by a 1989 study by Sidney Yoshida. It posited that front line workers were aware of 100% of the floor problems faced by an organisation, supervisors were aware of only 74%, middle managers were aware of only 9%, and senior executives were aware of only 4% of the problems.

The presenting problem is rarely the one that needs to be fixed…

Symptoms of problems may be useful, in that they may help identify a cause or causes, but in themselves the have little value. And the one thing that is for sure is that tackling symptoms alone is never going to solve the problem. Try giving aspirin to someone suffering with a headache. The symptoms may be controlled, but the person may die because of a much more serious ailment, the symptoms of which were being covered up by the aspirin treatment.

Employee engagement surveys will seldom produce any really valuable insights into causes, which are generally hidden from view. In the absence if any diagnostic capability, they produce a description of the current state as it is experienced by the employees – but they are just symptoms. Part of the issue here is the nature of the questions used in the surveys. Generally, they are questions calling for some sort of judgement. And direct, judgemental questions may identify symptoms but will never identify causes. And so valid improvement action becomes an impossibility. They also invite conscious and unconscious bias….

The opportunities to improve reside in your organisation, not anyone else’s

Finally, how does anyone know what constitutes a good result? Comparisons with other organisations or aggregated statistics showing norms are not going to help identify whether or not the organisation is a good performer, against a researched model of what good looks like – except in merely relative terms. “We are better than the average”. Is the average itself good? Or rubbish? “OK, so the average is getting better and so are we” Does that mean approaching close to perfection? Or climbing out of the pit of ‘deplorable’? (Whatever that might mean.)

What are the research data being used to identify an external standard for ‘good’? If there is one, to what degree does the research identify individual management practices that can make the difference between success and non-success? Back to symptoms and causes!

What if we enabled our people to lead the change?

What if there were an alternative approach? A very different means of generating data, one capable of providing insights into both symptoms and causes. What if that diagnostic processes also identified top priority, key causes, with no need for long reports. What if those insights were specific to each and every team in the organisation, thus bypassing the ‘iceberg’ problems. What if those teams were supported by external facilitators to define their own safe-to-try improvements, to improve the climate in their own team.

Moreover, high levels of diversity and psychological safety in decision-making groups guarantee high levels of inclusion. These groups always generate higher quality decisions and improvement where it is needed most – that is, where the problems are. And guess what happens to levels of engagement?

Enabling each and every team in the organisation to work on those areas of practice that will have greatest benefit to their Employee Engagement is the essence of The Vitality Index. You can read more about it here.

If you are curious about shifting the approach to improving Employee Engagement or if you can’t bear the thought of commissioning another report or if you’d just like a thinking partner to help you nail that purpose statement, then we’d love to help.

This post was written by Denis Bourne, co-founder or Organisational Vitality. Denis ran the research that the Vitality Index diagnostic is based upon. He has over 40 years’ experience helping organisations become more autonomous, innovative, and change enabled, and, as a happy consequence, also enjoying fantastic employee experience.