Culture; critical to success and stubborn to shift

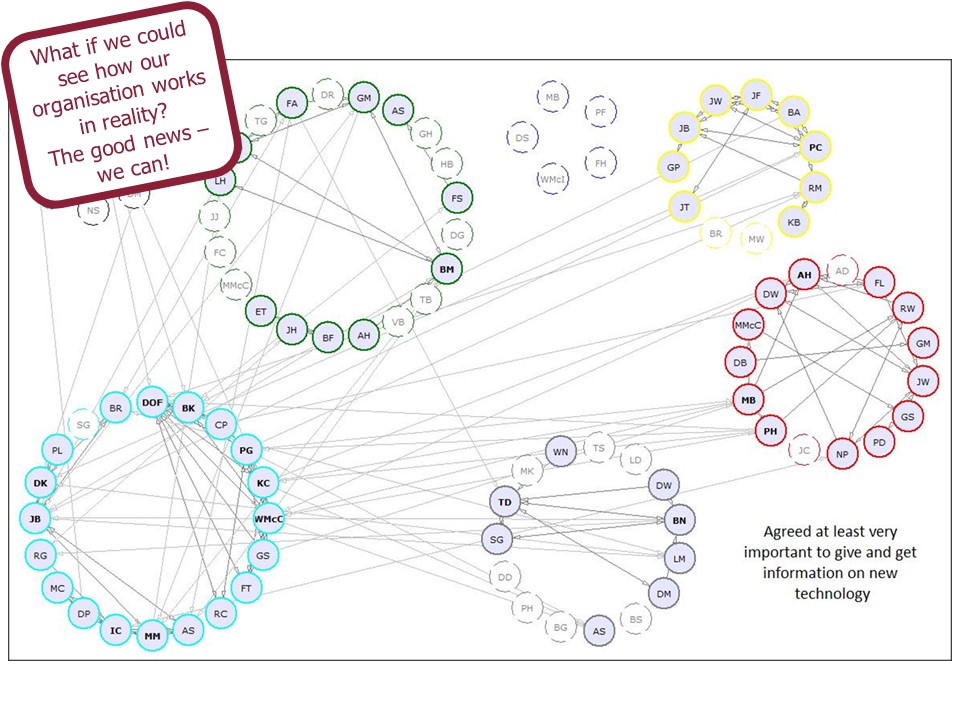

How many of you have written a business plan recently? For a new start-up, or a spin-off? Perhaps for a new iteration of your existing business, or a new subsidiary or venture into a new market? Hands up those of you who have included a section on the market, competition, the legal implications, the investment required, the return expected. All of you of course. And how many of you have included an organisation chart, board and ownership structures? Again, pretty much all of you. Now, how many of you have dedicated a section on how it feels to work in your organisation, to be a customer, how decisions are made, what type of conversations you might overhear, how information is shared, how feedback is given? In short, about the culture you intend to create?

I guess that not many hands are left up by now. And just to be clear, in all business plans I have ever produced – and I have written a lot – it was never part of my thinking either. Which is really peculiar, because if there is one thing crucial to a company’s success while at the same time hugely difficult to change once established, it is culture. And don’t say that culture is something you can’t (pre)determine or influence. Sure, there are intangible elements to it, but as culture is also the result of behaviours, language, processes and other actions, surely it is worth some advance thinking rather than just letting it happen?

There must be a tipping point at which an organisation changes from a start-up to an established organisation, somewhere in the scale-up phase, where this cultural DNA gets established. I like to refer to it as the stem-cell phase, in which an organisation can still take any shape and become any sort of creature it would like to be. But beyond which the roles, processes and habits begin to harden and reinforce each other, become stronger – in a way – and also more difficult to change.

Reed Hastings, of Netflix fame, learnt this lesson too. Reed’s first business venture pre-Netflix involved a software company called Pure Software. Although in the eyes of most of us still a very successful business, Hastings was frustrated with the loss of innovative spirit in the company as it grew larger. From a nimble, fun, entrepreneurial start-up, its success and resulting growth seemed to inevitably lead to more structure, more processes and procedures and a workforce that would suit that ‘safety-first’ environment best. Although the IPO of the company made Reed a wealthy man, he realised that in order to not end up with the same culture in his next venture, he would have to start out differently.

So at Netflix, he defined a few very clear principles that he hoped would ensure that the culture he would end up with would be as entrepreneurial and nimble as a start-up, despite its growing into a successful, large outfit. Under the mantra ‘Freedom & Responsibility’ he established principles around trust, transparency, feedback, decision-making, and various others. Ultimately, and not without some bumps in the road, these principles led to a very different culture, with the nimbleness he was after, and employees free to express their creativity and take ownership for their decisions. Not to mention a highly successful existence as the market leader in video streaming services.

What could this mean for you?

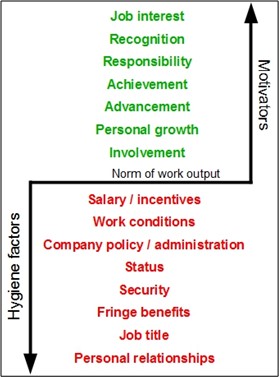

Well, if your organisation is a start-up/scale-up and still in its stem-cell phase, this is a good time to ask yourself some probing questions about what kind of organisation you would like to be. Are you happy to follow the conventional route: a nice hierarchy, plenty of policies & procedures, a top-down approach, some semblance of command and control? Then perhaps you will be just fine letting the organisation evolve as it grows. This default position is after all what most of us are familiar with and won’t challenge, even if it comes with the usual side-effects of bureaucracy, low staff engagement and loss of entrepreneurial spirit.

If that prospect fills you with horror, for instance because you believe that work should be an opportunity for people to express their whole selves, or because the nature of your business is such that your people will be better positioned if they are fully empowered and supported, or because you feel there is a competitive advantage to be had by doing things very differently and engaging the brains of your entire workforce to achieve that, or perhaps because of all of the above… Then there is still time to ask yourself some very fundamental questions and think through:

- What it should feel like to work in your – future – organisation or to be one of its customers

- What a good service, product or customer experience looks like, and what that requires from your organisation

- How – and where – decisions are made and what happens if something goes wrong

- How people interact with each other and feel psychologically safe

- What qualities you look for in your people, and who recruits as well as appraises them

- Who sets salaries and based on which criteria

- How you deal with information, sensitive or otherwise

- What the primary skills and behaviours you will be looking for in your management: supportive, coaching? Or fixing, directing, controlling?

- Etc…

… AS WELL AS how all of these factors work together in harmony so that they reinforce each other and ultimately lead to a successful business in all its aspects.

But what if your organisation is well past its stem-cell phase, is it doomed? Well, probably not. But a fundamental overhaul, a complete change of its culture, behaviours and practices will be a hard and lengthy process. My suggestion would be to not be over-ambitious: start small, with experiments based on what really helps the frontline in delivering better, with teams that are open to change. While at the same time shaping the desired behaviours at the top level of the organisation and start behaving yourself into a new way of thinking. With some luck, change within your teams will begin to take on a momentum of itself and, accelerated by the changed behaviours at the top, starts to nudge other parts of the organisation to move in the same direction.

Alternatively – and with large, complex organisations I believe this the more viable option – consider spinning out the part of the organisation most keen on cultural change and allow it to find its own path. Properly separated from the mother organisation and securely protected from being pulled back in by her gravitational force, this will give it the best possible chance to press the re-set button on its culture and truly reinvent the way it works.

So, my message to those of you lucky enough to be part of a nimble, creative start-up, where the CEO makes the coffee and job titles are still pretty meaningless, is this. Make the most of this time to visualise your future self. Picture yourself 5 years from now, with ten or a hundred times more colleagues. And start shaping the cultural building blocks for that organisation now, before it needs fixing.

This Blog was authored by Paul Jansen of Trustworks. He is passionate about helping organisations realise their full potential by unleashing the capabilities of their people and have built a reputation for introducing Buurtzorg’s concept of ‘self-management’ to many organisations in and outside the UK, predominantly in health and care providers, social enterprises and other organisations.